‘Until It is Spoken Back’

10 minutes

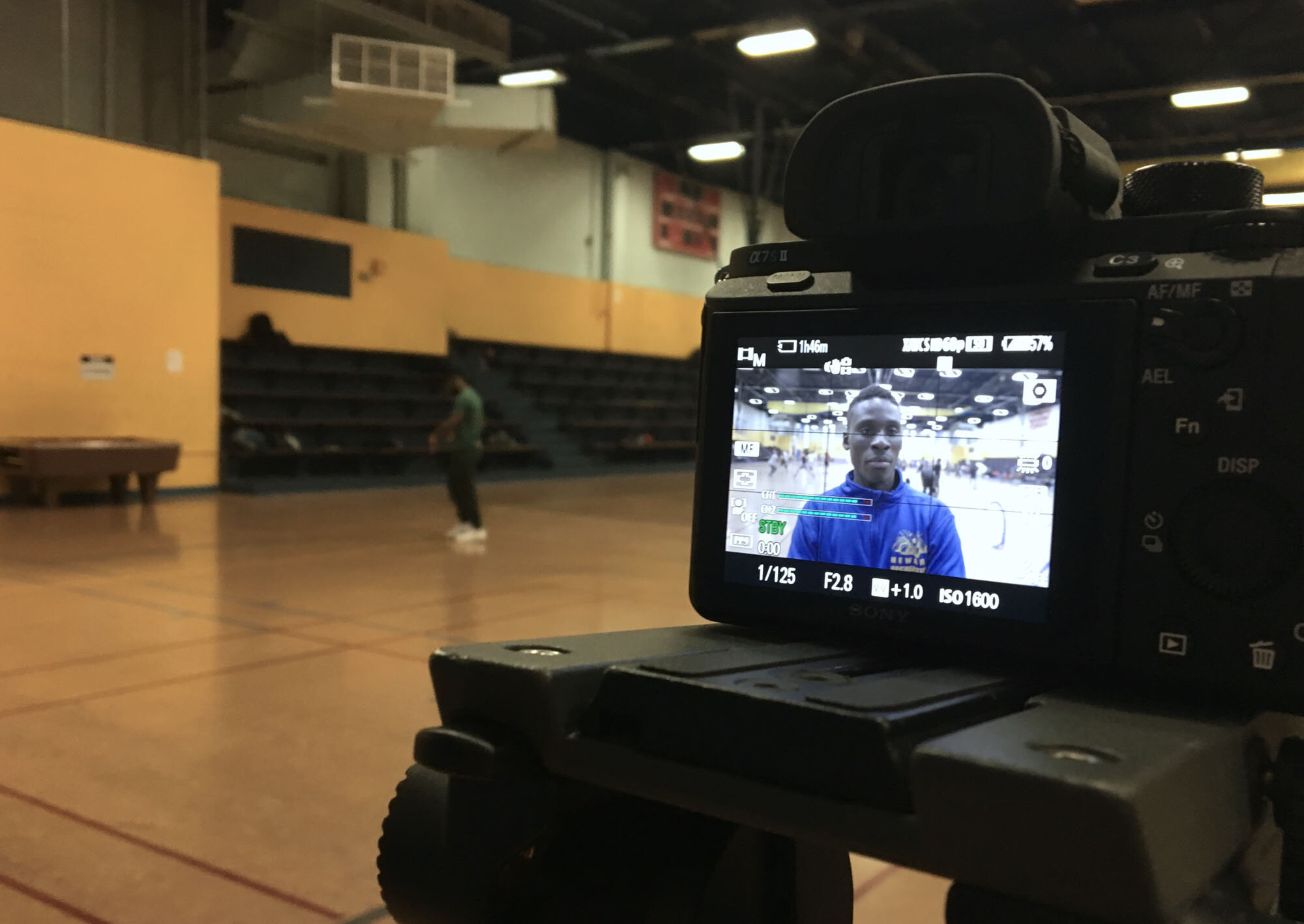

‘Until It is Spoken Back’ is a portrait of one young man and his educational journey from the USA to Nigeria and back again.

About the Film

‘Until It is Spoken Back’ started life as a research interview: I spoke to Paul, who the film centres on, as part of a research project exploring why Nigerian families living in the UK and USA may choose to send their children for an educational sojourn ‘back home’ in Nigeria.

In our interview, I was immediately struck by Paul’s powerful, articulate account of moving back and forth between the USA and Nigeria. His way with words vividly captured not only his own experiences, but also insightful reflections on deeper themes central to the research: racialised profiling, resilience, ambition. I thought it would be brilliant if those reflections could reach a wider audience: one of the things I dislike about academic work is that it often ends up translating fascinating human stories into dense, dry texts.

So I approached Paul to ask how he’d feel about me making something public based on his interview, and he was really enthusiastic. Over a long time, across continents, in fragments, the film very, very slowly came into being. Paul and I discussed various 10-minute audio versions of his story that emerged from the original 1.5 hour interview, and I worked with two incredibly talented filmmakers - Janelle Delia in the USA, and Terna Iwar in Nigeria - to shoot footage to accompany the audio. I learned that just like with writing, the edit is where the piece really emerges, and Janelle was my co-editor and teacher in that process.

Along the way, I felt some tension between the academic instinct to always say ‘it’s complicated’(!), and the limits of making a film centred on an individual. As a portrait based on Paul’s personal perspective, the film can never fully capture the complexity of the wider issues. Some of what you see in the film is quite specific to his story. Most importantly, his experience of corporal punishment, though core to his own memories and narrative, was not particularly typical in my research. In fact, in Lagos, corporal punishment has recently been banned by the state government, and it is relatively rare in the private schools to which most diaspora parents send their children. In relation to the painful incident of corporal punishment featured in the film, I would urge viewers to consider a few things: that punitive practices in Nigerian schools are in part a legacy of British colonialism, that bodily violence is only one form of violence in education, and that some migrant parents may prefer to subject their children to physical ‘disciplining’ than leave them to face US and UK carceral and immigration systems that give few second chances (as compellingly argued by Bledsoe and Sow, 2011).

In order to do justice to the diversity of tales of ‘homeland education’ in the Nigerian diaspora I would have had to make a much longer film - or a series of similar pieces featuring other young people. Though I can’t do that, I wanted to give a flavour of some other stories from the research. Each story below is in young people’s own words. Use the links below to explore these, and please feel free to get in touch if you have comments or questions.

Blessing - ‘I like the closeness between everybody’

Ade - ‘I didn’t think moving continent was appropriate punishment’

The project behind the film received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 750495.

Blessing’s Story - ‘I like the closeness between everybody’

The following is an edited narrative constructed from verbatim interview material.

My parents came to the UK when my mum was pregnant with me. But from when I remember, it was just me and my mum. My mum is like a nurse - a care worker. I was born in the UK, came back [to Nigeria] for a few years when I was young, lived in the UK from around age 5, and came back here [age 12].

Right now it's my grandparents that want me here. They believe that it's better for me to come here, just to relate to Nigerian culture. My Grandma thought that if I stayed [in the UK] for secondary school… well, when she came to the UK for a period, that was when she made the decision. She went on a bus, and she went to the upper deck, and saw some students just coming back from school. They were making a lot of noise, and my grandma was just like - she did not like it, she didn't want me to become like that.

At first I was supposed to go to a government school. My grandma had already started saying that, well, when you go there, you're going to come back, you're going to be totally different! Learn some respect. But then my aunty, she was like, there's no way I'm allowing her to go to that school, they would be too harsh. That she would prefer it if I went to this school [a private school]. But my grandma still wanted me to be a boarder, she didn't want me to be coming home and just slack off.

The first day I came here, I noticed people staring at me. And they were whispering! So that was really awkward, and I knew I couldn't go back home and tell my mum, and I knew my mum couldn't call that day, because it wasn't the weekend. So that first night I cried. I was just like, 'I want to go back home’.

And if I said anything, people would be like - ‘ehh?’ - I'd keep on repeating and repeating it, and they would be like 'I don't understand you’. Or they’ll start saying something about my accent. But eventually I got used to it, all of them are really nice, they take you in really easily, and they know how to crack jokes! I made friends with my roommate in hostel, so we're really close.

Well, to tell you the truth, sometimes I prefer being in hostel than at home. Cos my grandparents don't want me out of the compound. And most of the things I've known there, they've said it's wrong. Like, there, I didn't really used to wash the dishes, there was such a thing as a dishwasher… the modern world?! And then I came here, I dropped my plate in the sink, and when my grandma saw it, she shouted at me, like, 'where do you think you are? In London?! You have to wash you plates!'

Here, after school sometimes you just hang around in your room with your friends, or with our hostel mistress, we go to her room, sometimes she gives us snacks, and she has books in her room, and we’ll read. I like the closeness between everybody. In UK, like, if you're walking down the street, stuff like that, even your neighbours around you, you don't really relate with them. But in this neighbourhood here, everybody knows you. And this holiday now, it was so fun, because, with my uncle around, he's one of those uncles that likes buying stuff outside, like suya, or shawarma, stuff like that, like pizza.

Yeah, I miss the UK, the area I used to live. I’d take the 99 bus to Woolwich, and in Woolwich market I always used to love that section where you had the toys that blew bubbles, and the fidget spinners! But I also know it will be sad to leave here now. I feel like everyone in hostel is my sister. In the future I don’t want to stay in one place, I’d like travel around, to experience different cultures. I know when I get back to the UK I will have stories to tell.

Ade’s Story - ‘I didn’t think moving continent was appropriate punishment’

The following is an edited narrative constructed from verbatim interview material.

I was born in England, came to Nigeria aged 5 and did primary school here. The main reason I came for primary school was that my parents wanted me to have that roots, they thought that the way Nigerian people are brought up is better than English people. My Dad is a doctor and my mum is an artist. They both go back and forth a lot, every month or so. I went to this same school [an elite British curriculum school]. I went back to UK at 11. I’m 15.

This last summer, my mum lied to me - ‘you’ll come for summer, have a lot of tutors’. My grades had started to decline and going more and more down. I was distracted by wanting to fit in. When she said ‘you’re not going back’, I cried. I didn’t think that moving to another continent was an appropriate punishment for the things that I did.

[In the UK], it was more fun at school - which was the issue - nobody had aspirations. Just go home and play and sleep, and at school mess around. Because they were doing that, I started doing that. I was trying to fit in. I guess I felt a bit of an outsider coming back from Nigeria for the first time. My behaviour was very average - I never got into big amount of trouble until the last term of year 10. I wasn’t doing homework. The teachers started calling my mum, she was like ‘what is going on?’. She thought I’d fail if I stayed there, I thought I’d do OK.

It wasn’t that hard to come here as I did primary here. But I was sad to not say goodbye to my friends. And leaving playing rugby - I just made the regional team. In England you have a lot of freedom - it’s the thing I miss the most. You walk to school by yourself age 10. I used to leave the school and go for lunch. Here, school feels like a prison.

Learning was easier there, especially math, here I’m failing. It’s a lot harder, you start with 15 subjects - business. I open the test and just sit there scratching my head. Rumours spread here very fast. Someone asked me whether I was a drug dealer, and I said [heavily sarcastic voice] ‘yes, I was a drug dealer’, and then 2 hours later, like 3 people came up to me and were like ‘oh my God, you’re a drug dealer!’. No-one would think that your parents would send you to Nigeria for doing something good.

But I think - I’ve really thought about it, and I realise that they are doing it for my own good - I should be less angry about it, and try and see it from their perspective. If my child was in the same situation, I just realised that I would have done the same thing. Not because I want my child to be sad, because I want my child to have the best chance in life.

And even if you’re in England, if you have Nigerian parents - that land where your house is, is Nigeria, basically. Coming here refreshes that part… it grounds you. My family have a lot of connections here. One of my uncle is an executive at bank and said he’d offer me a job. But I know I want to live in England. I want my kids to leave the house and go to the park and play football.

Fola’s Story - ‘It’s tough, but I feel I made a good decision’

The following is an edited narrative constructed from verbatim interview material.

In the USA I lived in Florida, near Miami. They have good areas,and they have bad areas. We lived between the good and the bad areas. My parents were born here [in Nigeria] - they got married, had my two older sisters, and then they came to the US - my dad first, and then my mum came with my sisters. My dad got his masters, my mum became a nurse. They both work at the hospital.

I was good in school - I guess I just wasn't living up to my mother's expectations. Behaviour-wise. I guess I didn't see - because you were always surrounded by it - it was the lifestyle that you would live. It started in middle school. You know - you create these little groups. Just a little group, you know, a play group. But as we got older, it got more serious, some of my friends started hanging out with older boys - you know - drugs, stealing. Selling drugs inside of school.

But the main reason that my parents wanted to send me here was too much contact with the police. The first time I honestly didn't do anything wrong. It was like, 6 ‘o clock in the morning. I waiting for my school bus. That week, there was robberies in the area. Police came - and they drove past this way - drove past this way again, reversed, came back, like, at a high speed, angled the car at me - opened the car door, 'get on the floor, get on the floor' - he pulled a taser out. It was scary. Um, he handcuffed me. People were seeing me, on the road, in handcuffs on the floor. The school bus came, and everybody was looking at me.

The other time I got in contact with the police, it was a more serious thing. It was about 8 ‘o clock at night. I went out with my friend. I had stuff in my bag, marijuana. We saw the police come. And he stopped and he said - 'what are you doing out here at night?’ - ‘can I check your bag?’. And we - we ran. Eventually he caught up to us, and the first thing he did was - he pulled out his gun. And he put it to my chest. At that point I thought - I need to change. I kinda left all that stuff behind. It was still there, but I kind of you know, stopped doing a lot of it. It was kind of difficult, trying to take myself away.

My mum had a talk with me. She sat down and she spoke with me. She told me - basically, you're a good kid, you've got good grades. But it's not going to matter if you're dead, or in jail. So she said - what if I send you to Nigeria? I'd only been to Nigeria once, and that was when I was 10. I said - maybe I can try it. I wasn't really fond of the idea, but I thought - it's better than - as she said, dead or in jail.

They weren't expecting me to say yes. I just felt like it would be better. A better experience to go back to my home country and learn how they live and that, speak the language. Before I came, Nigeria was just an idea. There was really no connection because I [had only visited] for two weeks. But I was proud Nigerian. The values… I don’t know how to put it but, you know, African culture is heavy with respect. Respect, respect, respect, always respect. I understand Yoruba, but I can't really speak it well.

They just said it was a good school, grade wise. And spiritually, because it's a Christian school. My Grandma chose it. When I arrived - I don't know, I felt excited - really curious. I had to adjust to the heat, mosquitoes - a lot of mosquitoes. But I settled in pretty quickly. Because most of the stuff that they're doing here in Nigeria, my mum taught me. Like even though we had a washing machine, twice a month, my mum would make me wash clothes with my hands. I’ve made friends. Once my accent changed a bit, they became more open to me. They ask questions like, you know - how is life over there. I try to tell them as truthful as possible. You know, the bad parts, but there's all sorts of opportunities there for you.

I miss A/C, TV, my computer, my gaming systems. The internet, a wide variety of resources that could help you with everything. The food. You can't really leave the compound. Studying is lot tougher. The system is different, the way they teach is different. [In the US] we only have 7 subjects, Here we have 13 subjects - it's tiring. I'm not used to it. But little by little, I'll cope with it. I'm getting help from teachers. [One teacher] he just helps me mentally, like, to cope with everything - you know, things I should look out for. The work in the US was very easy. Here I've been experiencing working harder. I'm pretty sure that will benefit me. When I [return], everything should be easier for me. There's nothing else to do except read, read, read.

I told [my parents] I didn't want to go back until university - I just want to stay out of high school as long as possible. If I come back next year I'll meet my friends, the bad ones again. So I want to refrain from doing that. I feel like I made a good decision.

Victoria’s Story - ‘Here, they care if you’re learning’

The following is an edited narrative constructed from verbatim interview material.

I finished Year 11 in London. Over there I was doing alright, I was at the passing level, but you're mixed with different students, there were 30 in each set, and you always get the students who just don't want to learn. They'll just be annoying the teachers - so you wouldn't really learn much.

[My parents] were critical [of UK school], because they wanted us to have good jobs, to be a lawyer or be a doctor, all those things. It's bad to be all these minimal jobs. My dad was born and raised in Nigeria, my mum in Sierra Leone. They met in the UK. My Dad thought if we were all born abroad we would all have better opportunities.

In my GCSEs I got 5s [pass / ‘C’] in all my subjects, but in Maths I got a 3, I failed. I didn't like my GCSE grades, I wanted to get like, higher grades to do the course I wanted to study. I decided to come here, and start afresh and - have better opportunities. And I was always on at my Dad saying that I want to travel.

They chose this school because I had an aunty that works here, it was going to be easier for me to understand the system, get along, get by, know who to go with. I’m a day student and live with my aunty. In the family, everyone was welcoming. We got along instantly.

The weather was the worst thing when I first came last year. When I stepped off the plane - the heat. I came before to visit twice, but I was very young. And also, you have to be wise on the road. You have to always be looking in case there's bikes or buses coming, you have to really be streetwise. I was kind of scared, because I didn't know how to get along with the language, their own versions of slang [pidgin].

I've found it OK, but the things they learn here are more complex. The good thing is that here, they care if you're learning. If you want to be disrespectful, they'll send you out, and if you don't, they will help you to learn. In my secondary school [in the UK], some teachers were, I don't know, it's like they really didn't care if we learnt or not. Like, some of the teachers, I don't know, somehow - you would notice the difference with how they used to act. Most White students, they were nice to them, they would allow them. But Black students, they always see us as loud, playful, and that we're rough. But I guess it wasn't just the school, it was also - it could also be yourself as well. If you weren't motivated to study.

I miss the fact in the UK you can make a lot of friends, you're more free, you can hang out with whoever you want. Here, it's not like that - it's more like girls should mostly hang out with girls. I miss is having a phone, there being wifi literally everywhere. But, I don't know, everyone's always obsessed with social media. And they don't really prioritise things.

When I'm older, and have children in the future, I plan to bring them back as well. So they can get the same - I don't know how to word it, but, like the same learning I’ve got here. To be book-wise. To always be reading, so you don't have to struggle in life. Be respectful with elders. I realised what my parents went through, what it was like, being raised in Africa. My Dad was always telling us that everyone in Nigeria, they know what work is like. That they will strive to get it.

Here in Africa it's important to know what you want to do. You can't just say 'I don't know, wherever life takes me’: it's not acceptable here. Like, they must know what path they want to go on. What grade they desire, take it seriously, make your own decisions. They teach you life skills, they teach you, like, how you should act, how you should behave outside - like, you don't act reckless. You need to act smart, dress smart, dress appropriate here. You need to act you age and maybe older, you need to basically be wise.

Like, it's shaped me to speak for myself, to be my own person. It's taught me how to be independent. And - really, it's taught me a lot of things! Back home I wasn't independent - I learned how to cook now, a normal stew that you eat with rice, and I'm currently trying to learn how to make egusi soup, that one's difficult.